Next: Hermitian Conjugate of an Up: Eigenfunctions, Eigenvalues and Vector Previous: Eigenfunctions, Eigenvalues and Vector Contents

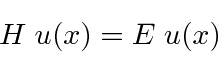

the eigenfunction,

giving a constant

the eigenfunction,

giving a constant

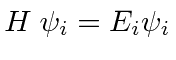

Usually, for bound states, there are many eigenfunction solutions (denoted here by the index

![]() ).

).

|

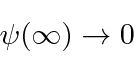

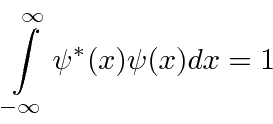

For states representing one particle (particularly bound states) we must

require that the solutions be normalizable.

Solutions that are not normalizable must be discarded.

A normalizable wave function must go to zero at infinity.

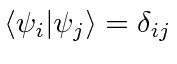

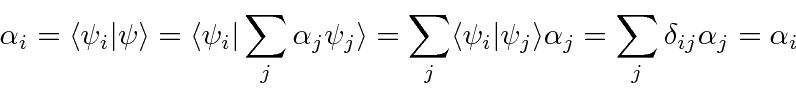

We will prove later that the eigenfunctions are orthogonal to each other.

|

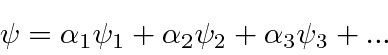

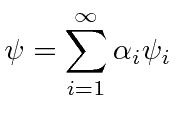

We will assume that the

eigenfunctions form a complete set

so that any function can be written as a linear combination of them.

|

Since the eigenfunctions are orthogonal, we can easily

compute the coefficients

in the expansion of an arbitrary wave function

![]() .

.

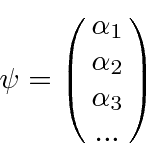

We will later think of the eigenfunctions as unit

vectors in a vector space.

The arbitrary wave function

![]() is then a vector in that space.

is then a vector in that space.

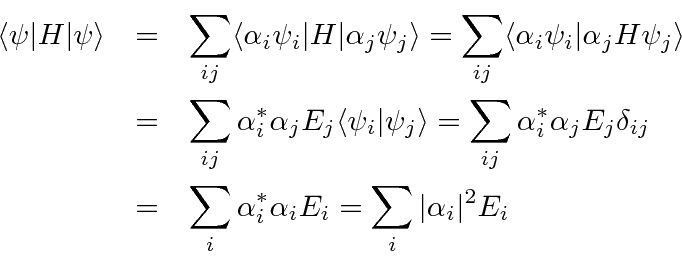

It is instructive to compute the expectation value of the Hamiltonianusing the expansion of

![]() and the orthonormality of the eigenfunctions.

and the orthonormality of the eigenfunctions.

obviously give the probability.

obviously give the probability.

Jim Branson 2013-04-22