Next: Identical Particles Up: Extending QM to Two Previous: Quantum Mechanics in Three Contents

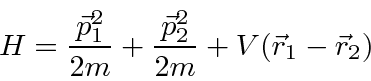

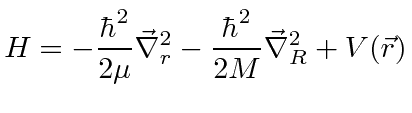

The generalization of the Hamiltonian to three dimensions is simple.

|

|

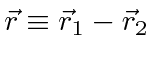

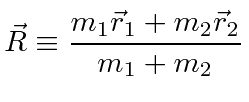

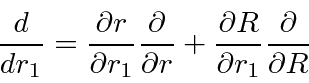

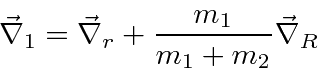

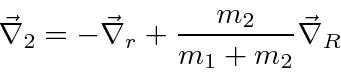

We will use the chain rule to transform our Hamiltonian.

As a simple example, if we were working in one dimension we might

use the chain rule like this.

In three dimensions we would have.

Putting this into the Hamiltonian we get

![\begin{displaymath}\bgroup\color{black}H={-\hbar^2\over 2m_1}\left[\vec{\nabla}_...

...1\over m_1+m_2}\vec{\nabla}_r\cdot\vec{\nabla}_R\right] \egroup\end{displaymath}](img1600.png)

![\begin{displaymath}\bgroup\color{black}\qquad +{-\hbar^2\over 2m_2}\left[\vec{\n...

...m_2}\vec{\nabla}_r\cdot\vec{\nabla}_R\right]+V(\vec{r}) \egroup\end{displaymath}](img1601.png)

![\begin{displaymath}\bgroup\color{black}H=-\hbar^2\left[ \left({1\over 2m_1}+{1\o...

...2\over 2(m_1+m_2)^2}\vec{\nabla}_R^2\right]+V(\vec{r}) .\egroup\end{displaymath}](img1602.png)

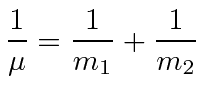

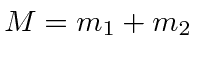

Defining the reduced mass

![]()

|

|

|

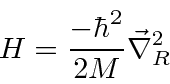

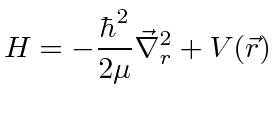

The Hamiltonian actually separates into two problems:

the motion of the center of mass as a free particle

|

This is exactly the same separation that we would make in classical physics.

Jim Branson 2013-04-22