Next: Hole Theory and Charge Up: Dirac Equation Previous: Solution of the Dirac Contents

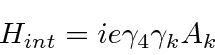

In the Dirac theory, we have only one term in the interaction Hamiltonian,

The initial and final states are definite momentum states, as are the intermediate electron states.

We shall first do the calculation assuming no electrons from the ``negative energy'' sea participate,

other than to exclude transitions to those ``negative energy'' states.

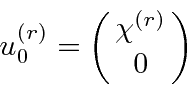

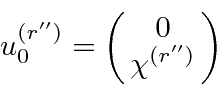

The initial and final states are therefore the positive energy plane wave states

for

for

.

The intermediate states must also be positive energy states since the ``negative energy'' states are all filled.

.

The intermediate states must also be positive energy states since the ``negative energy'' states are all filled.

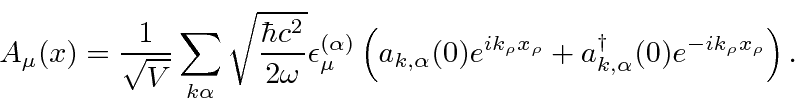

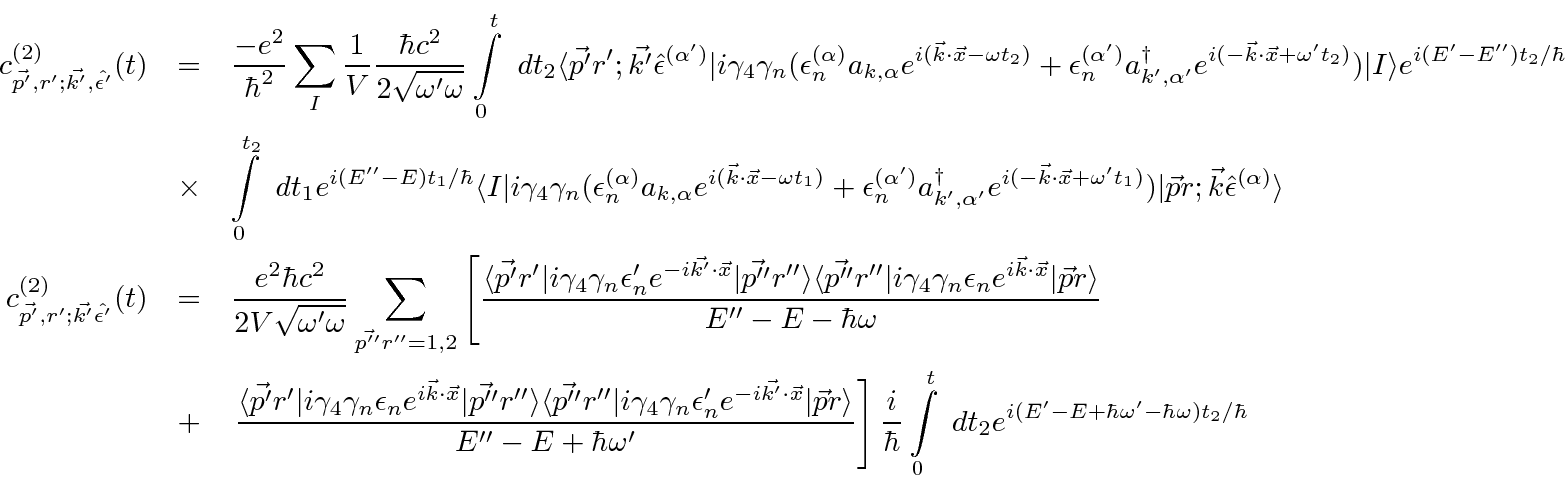

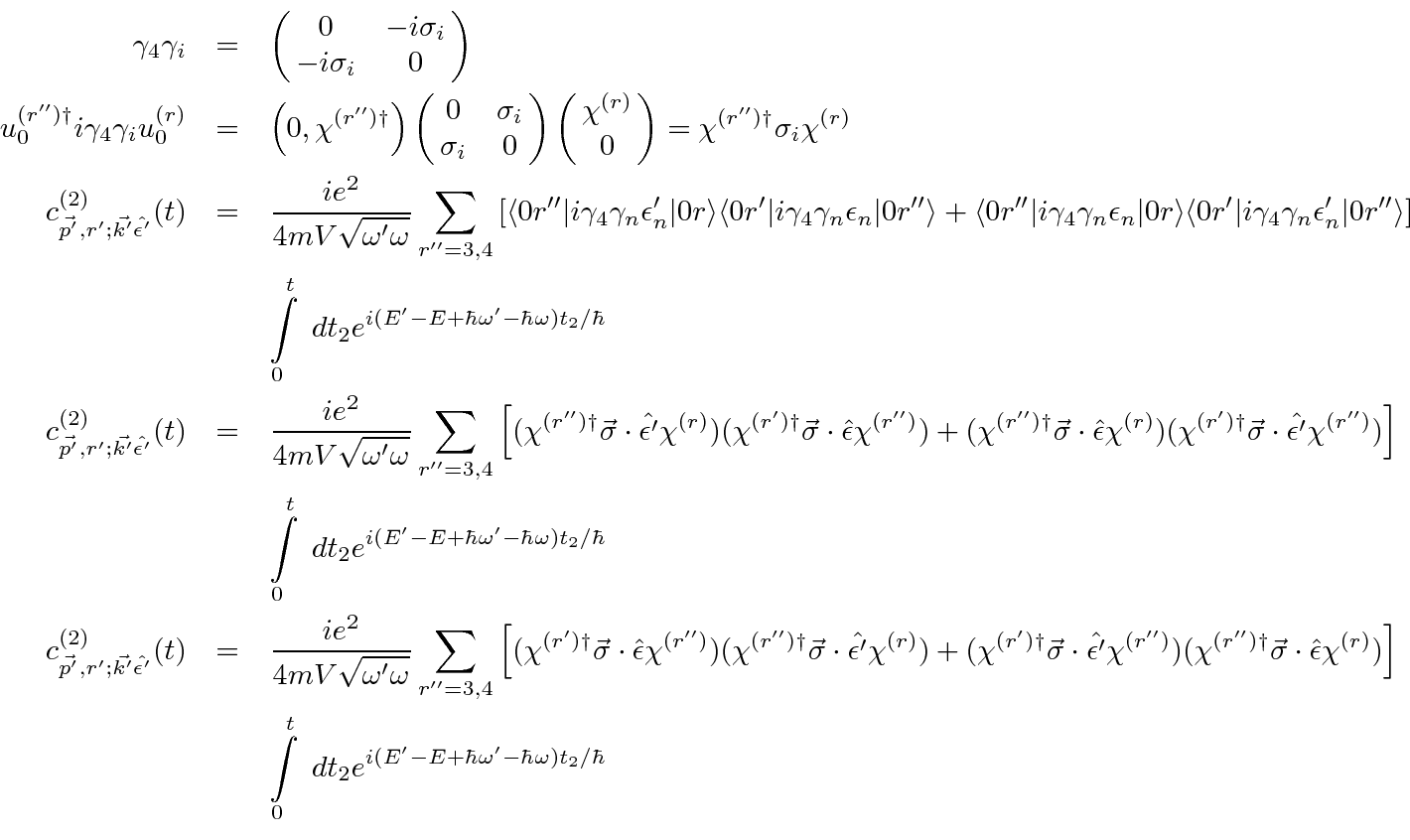

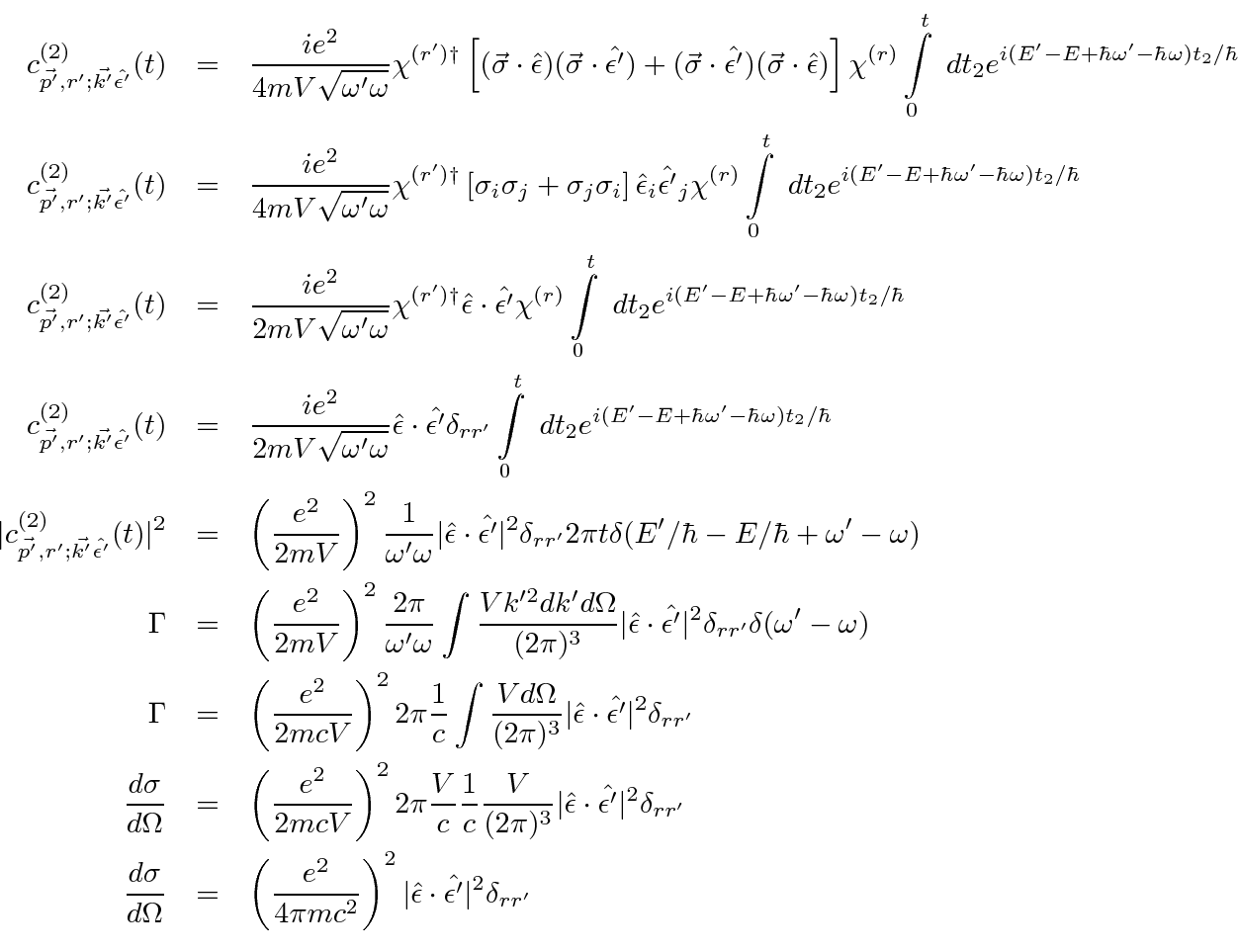

The computation of the scattering cross section follows the same steps made in the development of the Krammers-Heisenberg

formula for photon scattering.

There is no

![]() term so we are just computing the two second order terms.

term so we are just computing the two second order terms.

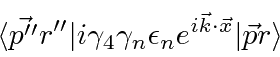

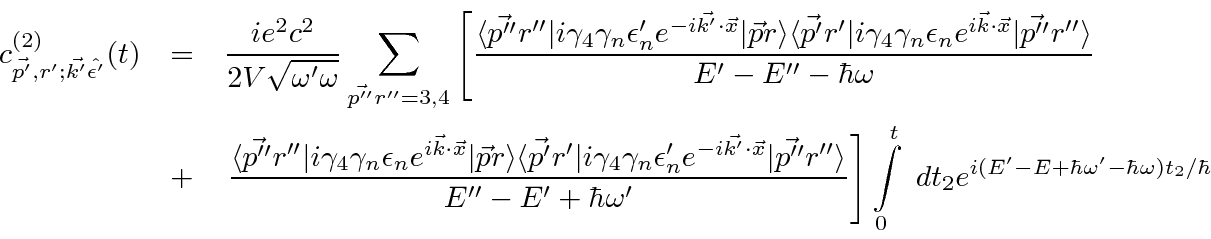

Now lets take a look at one of the matrix elements.

Assume the initial state electron is at rest and that the photon momentum is small.

and

and

.

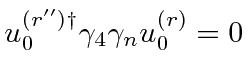

It turns out that

.

It turns out that

, so that the cross section is zero in this limit.

, so that the cross section is zero in this limit.

spinors to

spinors to

spinors because of its off diagonal nature.

So, the calculation yields zero for a cross section in contradiction to the other two calculations.

In fact, since the photon momentum is not quite zero, there is a small contribution, but far too small.

spinors because of its off diagonal nature.

So, the calculation yields zero for a cross section in contradiction to the other two calculations.

In fact, since the photon momentum is not quite zero, there is a small contribution, but far too small.

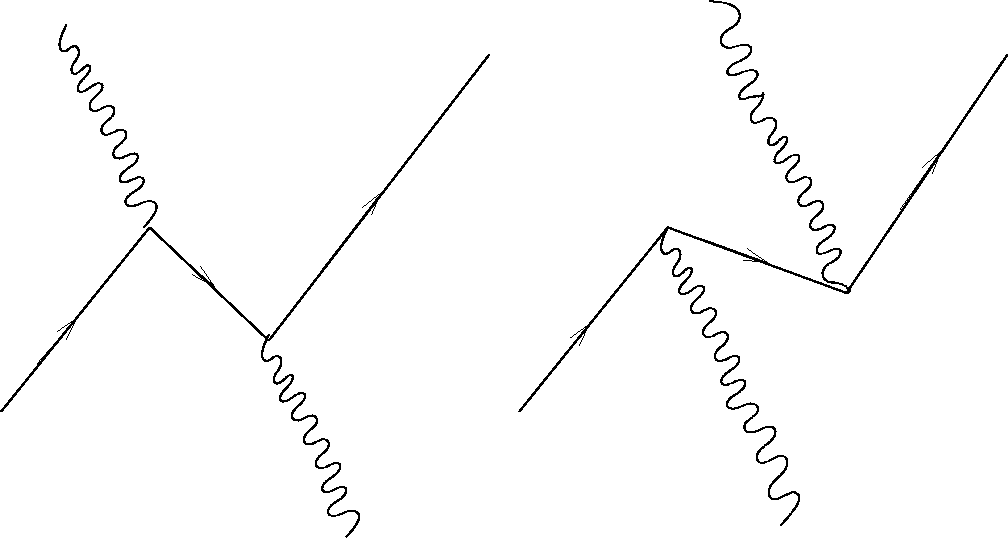

The above calculation misses some important terms due to the ``negative energy'' sea. There are additional terms if we consider the possibility that the photon can elevate a ``negative energy'' electron to have positive energy.

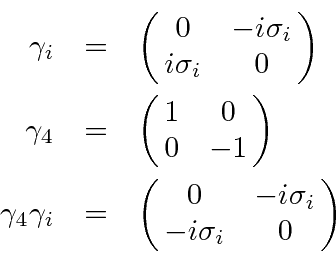

matrix connects positive energy and ``negative energy'' states.

matrix connects positive energy and ``negative energy'' states.

, the final electron (approximately)

at rest, and hence the intermediate electron at rest, due to a delta function of momentum conservation

that comes out of the spatial integral.

, the final electron (approximately)

at rest, and hence the intermediate electron at rest, due to a delta function of momentum conservation

that comes out of the spatial integral.

Let the positive energy spinors be written as

connect the positive and ``negative energy'' spinors so that the amplitude can be written in

terms of two component spinors and Pauli matrices.

connect the positive and ``negative energy'' spinors so that the amplitude can be written in

terms of two component spinors and Pauli matrices.

Jim Branson 2013-04-22