Next: Hyperfine Splitting in a Up: Hyperfine Structure Previous: Hyperfine Structure Contents

We can think of the nucleus as a single particle with spin

![]() .

This particle is actually made up of protons and neutrons which are

both spin

.

This particle is actually made up of protons and neutrons which are

both spin

![]() particles.

The protons and neutrons in turn are made of spin

particles.

The protons and neutrons in turn are made of spin

![]() quarks.

The magnetic dipole moment due to the nuclear spin is much smaller than

that of the electron because the mass appears in the denominator.

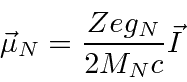

The magnetic moment of the nucleus is

quarks.

The magnetic dipole moment due to the nuclear spin is much smaller than

that of the electron because the mass appears in the denominator.

The magnetic moment of the nucleus is

.

This is the nucleus of hydrogen upon which we will concentrate.

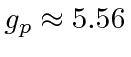

Even though the neutron is neutral, the gyromagnetic ratio is about -3.83.

(The quarks have gyromagnetic ratios of 2 (plus corrections) like the electron but the

problem is complicated by the strong interactions which make it hard to define a quark's mass.)

We can compute (to some accuracy) the gyromagnetic ratio of nuclei from that of protons and neutrons

as we can compute the proton's gyromagnetic ratio from its quark constituents.

.

This is the nucleus of hydrogen upon which we will concentrate.

Even though the neutron is neutral, the gyromagnetic ratio is about -3.83.

(The quarks have gyromagnetic ratios of 2 (plus corrections) like the electron but the

problem is complicated by the strong interactions which make it hard to define a quark's mass.)

We can compute (to some accuracy) the gyromagnetic ratio of nuclei from that of protons and neutrons

as we can compute the proton's gyromagnetic ratio from its quark constituents.

In any case, the nuclear dipole moment is about 1000 times smaller than that for e-spin or

![]() .

We will calculate

.

We will calculate

![]() for

for

![]() states (see Condon and Shortley for more details).

This is particularly important because it will break the degeneracy of the Hydrogen ground state.

states (see Condon and Shortley for more details).

This is particularly important because it will break the degeneracy of the Hydrogen ground state.

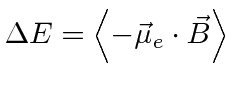

To get the perturbation, we should

find

![]() from

from

![]() (see Gasiorowicz page 287) then

calculate the energy change in first order perturbation theory

(see Gasiorowicz page 287) then

calculate the energy change in first order perturbation theory

.

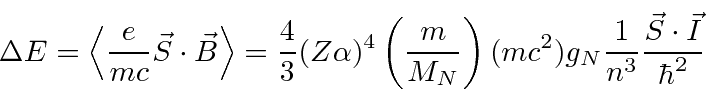

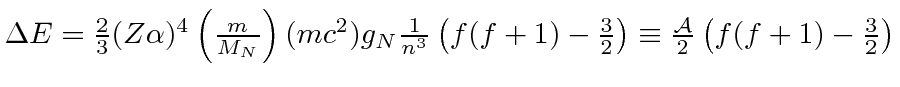

Calculating

the energy shift for

.

Calculating

the energy shift for

![]() states.

states.

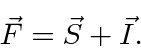

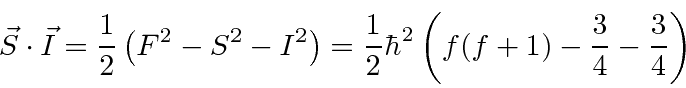

Now, just as in the case of the

![]() , spin-orbit interaction,

we will define the total angular momentum

, spin-orbit interaction,

we will define the total angular momentum

that the hyperfine perturbation

will be diagonal.

In essence, we are doing degenerate state perturbation theory.

We could diagonalize the 4 by 4 matrix for the perturbation to solve the problem or

we can use what we know to pick the right states to start with.

Again like the spin orbit interaction, the total angular momentum states will be

the right states because we can write the perturbation in terms of

quantum numbers of those states.

that the hyperfine perturbation

will be diagonal.

In essence, we are doing degenerate state perturbation theory.

We could diagonalize the 4 by 4 matrix for the perturbation to solve the problem or

we can use what we know to pick the right states to start with.

Again like the spin orbit interaction, the total angular momentum states will be

the right states because we can write the perturbation in terms of

quantum numbers of those states.

|

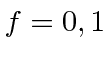

For the hydrogen ground state we are just adding two spin

![]() particles so the

possible values are

particles so the

possible values are

.

.

* Example:

The Hyperfine Splitting of the Hydrogen Ground State.*

The transition between the two states gives rise to EM waves with

![]() cm.

cm.

Jim Branson 2013-04-22